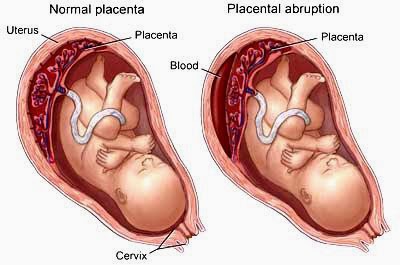

Abruptio placentae also called placental abruption occur when the placenta prematurely separates from the uterine wall, usually after the 20th week of gestation, producing hemorrhage. This disorder may be classified according to the degree of placental separation and the severity of maternal and fetal symptoms. It is characterized by a triad of symptoms: vaginal bleeding, uterine hypertonus, and fetal distress. It can occur during the prenatal or intrapartum period. Abruptio placentae is most common in multigravidas usually in women older than age 35 and is a common cause of bleeding during the second half of pregnancy. On heavy maternal bleeding generally necessitates termination of the pregnancy. The fetal prognosis depends on the gestational age and amount of blood lost. The maternal prognosis is good if hemorrhage can be controlled.

Grading System for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption)

- Grade 0 Less than 10% of the total placental surface has detached; the patient has no symptoms; however, a small retroplacental clot is noted at birth.

- Grade I approximately 10%–20% of the total placental surface has detached; vaginal bleeding and mild uterine tenderness are noted; however, the mother and fetus are in no distress.

- Grade II Approximately 20%–50% of the total placental surface has detached; the patient has uterine tenderness and tetany; bleeding can be concealed or is obvious; signs of fetal distress are noted; the mother is not in hypovolemic shock.

- Grade III More than 50% of the placental surface has detached; uterine tetany is severe; bleeding can be concealed or is obvious; the mother is in shock and often experiencing coagulopathy; fetal death occurs.

Central abruption, the separation occurs in the middle, and bleeding is trapped

Between the detached placenta and the uterus, concealing the hemorrhage

Marginal abruption, separation begins at the periphery and bleeding accumulates between

The membranes and the uterus and eventually passes through the cervix, becoming an external hemorrhage.

Causes for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption)

The cause of abruptio placentae is unknown; however, any condition that causes vascular changes at the placental level may contribute to premature separation of the placenta. Predisposing factors include:

Traumatic injury.

Placental site bleeding from a needle puncture during amniocentesis,

Chronic or pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Multiparity

Short umbilical cord

Dietary deficiency

Smoking

Advanced maternal age

Pressure on the vena cava from an enlarged uterus.

The spontaneous rupture of blood vessels at the placental bed may result from a lack of resiliency or to abnormal changes in the uterine vasculature. The condition may be complicated by hypertension or by an enlarged uterus that can’t contract sufficiently to seal off the torn vessels. Consequently, bleeding continues unchecked, possibly shearing off the placenta partially or completely.

Complications for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption)

Hemorrhage and shock.

Renal failure,

Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Maternal and fetal death.

Nursing Assessment

Abruptio placentae produce a wide range of clinical effects, depending on the extent of placental separation and the amount of blood lost from maternal circulation.

Obtain patient history obstetric history. Determine the date of the last menstrual period to calculate the estimated day of delivery and gestational age of the infant. Inquire about alcohol, tobacco, and drug usage, and any trauma or abuse situations during pregnancy

Mild Abruptio placentae with marginal separation usually report mild to moderate vaginal bleeding, vague lower abdominal discomfort, and mild to moderate abdominal tenderness.

Moderate Abruptio placentae are about 50% placental separation usually report continuous abdominal pain and moderate, dark red vaginal bleeding. Onset of symptoms may be gradual or abrupt. Vital signs may indicate impending shock. Palpation reveals a tender uterus that remains firm between contractions.

Severe Abruptio placentae about 70% placental separations patient usually report abrupt onset of agonizing, unremitting uterine pain (described as tearing or knifelike) and moderate vaginal bleeding. Vital signs indicate rapidly progressive shock. Palpation reveals a tender uterus with board like rigidity. Uterine size may increase in severe concealed abruptions.

Psychosocial Assessment to understanding patient’s situation and also the significant other’s degree of anxiety, coping ability, and willingness to support the patient

Diagnostic tests for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption)

Pelvic examination under double setup

Ultrasonography

Decreased hemoglobin level

Decreased platelet count.

Periodic assays for fibrin split products aid in monitoring the progression of abruptio placentae and in detecting DIC.

Treatment for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption)

Medical Treatment management goals of abruptio placentae are to assess, control, and restore the amount of blood lost and to deliver a viable infant and prevent coagulation disorders.

After determining the severity of placental abruption and appropriate fluid and blood replacement, prompt cesarean delivery is necessary if the fetus is in distress. If the fetus isn’t in distress, monitoring continues; delivery is usually performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

Nursing diagnosis

Primary nursing diagnosis fluid volume deficit related to blood loss. Common nursing diagnosis fond in Nursing Care Plans for Abruptio Placentae (placenta abruption):

Acute pain

Anxiety

Deficient fluid volume

Dysfunctional grieving

Fear

Ineffective coping

Ineffective tissue perfusion: Cardiopulmonary

Key outcomes the patient will:

Express feelings of comfort.

Express feelings of reduced anxiety.

Communicate feelings about the situation.

Discuss fears and concerns.

Use available support systems, such as family and friends, to aid in coping.

Remain hemodynamically stable.

Patient’s fluid volume will remain within normal parameters.

Nursing interventions

Monitor Vital sign; blood pressure, pulse rate, respirations, central venous pressure, intake and output, and amount of vaginal bleeding.

Monitor fetal heart rate electronically.

If vaginal delivery is elected, provide emotional support during labor.

Because of the neonate’s prematurity, the mother may not receive an analgesic during labor and may experience intense pain. Reassure the patient of her progress through labor, and keep her informed of the fetus’s condition.

Encourage the patient and her family to verbalize their feelings. Help them to develop effective coping strategies. Refer them for counseling, if necessary.

Patient teaching discharge and home healthcare guidelines

Teach the patient to identify and report signs of placental abruption, such as bleeding and cramping.

Explain procedures and treatments to allay patient’s anxiety.

Teach the patient to notify the doctor and come to the hospital immediately if she experiences any bleeding or contractions.

Prepare the patient and her family for the possibility of an emergency cesarean delivery, the delivery of a premature neonate, and the changes to expect in the postpartum period. Offer emotional support and an honest assessment of the situation.

Tactfully discuss the possibility of neonatal death. Inform the patient that the neonate’s survival depends primarily on gestational age, the amount of blood lost, and associated hypertensive disorders.

Inform the patient that frequent monitoring and prompt management greatly reduce the risk of death.

After Postpartum Patient teaching discharge and home healthcare guidelines

Give the usual postpartum instructions for avoiding complications. Inform the patient that she is at much higher risk of developing abruptio placentae in subsequent Pregnancies. Instruct the patient on how to provide safe care of the infant. Provide a list of referrals to the patient and significant others to help them manage their loss, If the fetus has not Survived